The bold Mexican composer finds herself within the highlight — lastly

Gabriela Ortiz is occupying the Composer’s Chair at Carnegie Corridor this season.

Marta Arteaga

disguise caption

toggle caption

Marta Arteaga

Composer Gabriela Ortiz has paid some dues — and now she’s amassing. Earlier in her profession, she walked out on sexist professors, rebuffed condescending musicians and as soon as waited hours to fulfill with a conductor in hopes of merely listening to her personal music carried out. In 2019, she underwent therapy for colon most cancers, which is now in remission.

In the present day, the 59-year-old Mexico Metropolis native is having fun with some well-deserved recognition. Ortiz has simply begun a year-long composer’s residency at Carnegie Corridor, the place her music and her programming will probably be heard in a wide range of contexts. She’s serving in related roles this season on the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia and the Castilla y León Symphony in Spain.

She’s additionally cultivated a crushing schedule. Prior to now 4 years, Ortiz has premiered at the very least 10 main orchestral works, half of them championed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic and its star conductor Gustavo Dudamel, who has referred to as her one of the crucial gifted composers on the planet and who will lead Ortiz’s new cello concerto, written for Alisa Weilerstein, at Carnegie Corridor on Oct. 9. Revolución Diamantina, a latest album of her works carried out with Dudamel and his orchestra, has earned glowing evaluations for the way deftly it combines an array of musical languages, from excessive European modernism to the roots of Latin American people.

Music, and hard-won confidence, run within the Ortiz household. Her grandfather, a classical music fanatic, moved to Mexico from Basque Nation, Spain, and noticed Gustav Mahler conduct in New York whereas dwelling on the East Coast. Ortiz’s mother and father co-founded Los Folkloristas, the celebrated band devoted to Latin American people music and analysis, and she or he discovered to play devices within the group’s outreach studying middle for kids. With the piano as her main instrument, Ortiz realized early on that the lifetime of a live performance pianist was maybe past her attain — however the thought of composing blossomed after an early encounter with Béla Bartók’s music, and from there, nothing might cease her ambitions.

From her studio in Mexico Metropolis, Ortiz joined a video chat for a far-ranging dialog concerning the function people music performs in her work, the significance of talking your thoughts in your artwork, and what it actually means to be a composer from Mexico.

This interview has been edited for size and readability.

Tom Huizenga: I first heard your music in 1998 at a Kronos Quartet live performance, the place the group performed Altar de Muertos. Within the ultimate motion of that piece, there’s a reference to an Indigenous music tradition from Mexico — a Huichol people melody from the state of Nayarit. That very same melody has now appeared in at the very least two extra of your items, together with the latest Kauyumari. What attracted you to this people tune?

Gabriela Ortiz: I first heard it on a Huichol recording. Usually I by no means use direct quotations, however on this case, as a result of the melody was very enticing, I simply had to make use of it. The [folk musicians] play a violin that solely has two strings, so I harmonized that melody and developed it rhythmically. The melody repeats and repeats — and for the Huichol individuals, repetition is essential, as a result of it is music you play in peyote ceremonies the place hallucinations are a approach to contact ancestors.

Your mother and father had been founding members of the band Los Folkloristas, which specialised in Latin American people music; was using that melody influenced by your childhood experiences?

No, I by no means heard Los Folkloristas play Huichol music. Usually, the folks music that we hear in Mexico is a mix between European, Indigenous and African — these are the three fundamental roots. This got here later, once I obtained the recording from the Institute of Anthropology, and I simply fell in love with it.

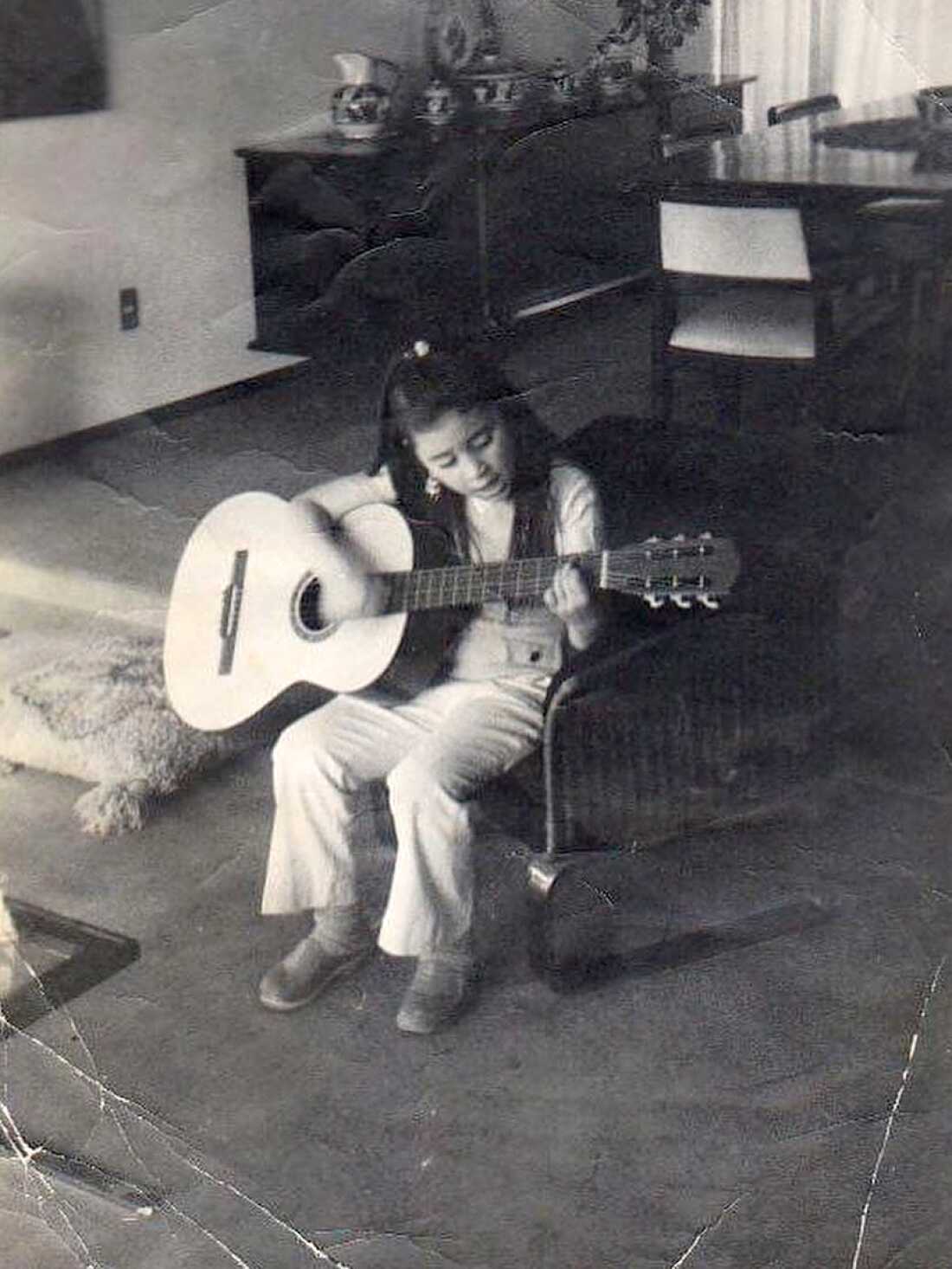

Gabriela Ortiz discovered to play the guitar as youngster, aided by her mother and father, who cofounded the Latin American musical group Los Folkloristas.

Courtesy of the artist

disguise caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of the artist

What was it like rising up in a family steeped in people music?

It was enjoyable, as a result of among the rehearsals occurred in our home. My father was an architect, so we had a giant home, and within the basement was a studio filled with devices — guitars, a charango and drums and completely different devices, not solely from Mexico however from Latin America. They’d rehearsals within the evenings, and naturally my mother and father mentioned, “Go to mattress!” However I by no means went to mattress; I stayed within the corridor making an attempt to take heed to the music.

I additionally met essential musicians, like Atahualpa Yupanqui and Mercedes Sosa, who got here to our home. Additionally Victor Jara, the Chilean singer — the one time he got here to Mexico, he stayed in our home. Throughout the dictatorship of Pinochet, they captured him and minimize off his arms. I bear in mind my father crying when somebody referred to as to inform him that Victor Jara had died; he was shouting, “No, no!” and I did not know what was occurring. So sure, it was essential for me not solely musically, but additionally politically.

Did you ever play within the group along with your mother and father?

Not within the group. Los Folkloristas had a college for individuals who wished to be taught people music, so I performed guitar and charango within the youngsters’s part. Typically I sat in with them for enjoyable, however by no means in a live performance corridor.

Had been you listening to any classical music in these early days?

Completely. My mom performed piano for 18 years; she was an excellent sight reader. And I bear in mind my father took me to see a live performance with Eduardo Mata, the conductor who was one in every of our biggest administrators within the historical past of music in Mexico. He was conducting the London Symphony, and I keep in mind that they performed Manuel de Falla’s El sombrero de tres picos and I used to be like, “Oh my God!” I simply cherished it.

My father was an architect, however he wished to be a classical composer. He could not do it as a result of my mom died very younger, and he obtained depressed and mentioned, “Properly, I do not know if I will be a composer, however my daughter might be a composer.” So, out of the blue he put all of his considering into my profession.

Whose thought was it so that you can grow to be a composer?

I bear in mind once I was 7 or 8 years previous, my mom mentioned, “I am seeing that you simply love music and also you play the guitar. Why don’t you begin studying the piano, and learn to learn music?” So I began piano classes. Once I was about 13 years previous I modified to a brand new trainer, and this girl was like a Mexican model of Nadia Boulanger. She was an excellent trainer of concord and solfège, and she or he launched me to Béla Bartók. On the time, I used to be taking part in Mozart, Bach and Schumann, however once I first heard Bartók’s music I mentioned, “Wow, what is that this?” I instantly had a connection, in all probability due to the rhythm and the modal language. It was a very completely different factor. I mentioned, “I need to write little items for piano like Bartók,” so I began composing for the piano. Then I noticed, I am not going to be a live performance pianist — that is not my purpose. I need to be a composer.

At 13, Ortiz was launched to the music of Béla Bartók by a piano trainer, which impressed her to put in writing her personal piano items.

Marta Arteaga

disguise caption

toggle caption

Marta Arteaga

I really feel like Mexico remains to be slightly beneath the radar when it comes to individuals understanding about its wealthy historical past in classical music. Carlos Chávez or probably Silvestre Revueltas are the one composers many individuals know, even classical followers. Why is that?

There isn’t any curiosity. Once I was finding out in England, they did not know who Revueltas or Chávez was. They didn’t care about what was occurring in Latin America. Additionally, in Latin American establishments, you be taught Western European music, principally. It’s a part of the canon in all the schools. German Romanticism is strongly emphasised — Beethoven, Bach. However do we actually know the entire contributions by Villa-Lobos or by Ginastera, and even by Revueltas?

Many younger Latin American composers transfer to Europe, as a result of they need their music to be performed. They compromise their language as a result of they’re composing in a really European model. For me, that’s one of many different issues. I imply, after all, in the event that they need to compose like that, it’s OK. However lots of them compose within the spectralism model, like that of Tristan Murail or Helmut Lachenmann.

You train on the Nationwide Autonomous College in Mexico Metropolis. Do your college students select to compose in that European model?

A few of them. After all, in the event that they need to compose like that, there may be nothing that I can do — I’ve to respect their freedom, and I can solely communicate for myself. That model does not work for me; I do not belong to that. I used to be not born in Germany, so why do I’ve to compose like Lachenmann or Wolfgang Rihm? I am completely completely different.

This leads me to surprise: What does it imply to you to be a Mexican composer? I believe it was Virgil Thomson who was as soon as requested the way you outline American music, and he mentioned: “It’s music made by somebody with an American passport.” Is it that straightforward for you, or is there extra to it?

That is a very powerful factor: Once I do my music, I write what I’ve to say. I am not considering, “Okay, that is going to sound actually Mexican” — by no means. If I take advantage of a Huichol melody, it’s as a result of I actually prefer it. But when I discover a melody from Bali, possibly I’ll use it as properly. What’s essential is what you do with that.

It is very tough to outline Mexico, as a result of Mexico is large. It’s not the identical within the North as within the South or the middle. One of many fundamental issues is that individuals attempt to put a particular label on Latin American music, and that is completely improper as a result of Latin America is so completely different — Argentina from Mexico, or from Venezuela, or the Caribbean international locations.

At a 2019 rehearsal of her work Antrópolis, Ortiz discusses a percussion passage with conductor Carlos Miguel Prieto and percussionist Gabriela Jimenez of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Minería in Mexico Metropolis.

Bernardo Arcos Mijailidis

disguise caption

toggle caption

Bernardo Arcos Mijailidis

I really feel like your music has a singular language, however there are influences as properly. Firstly, I hear Stravinsky — these stabbing rhythms in your ballet Revolución Diamantina, additionally in Téenek and Clara. What attracts you to Stravinsky?

Stravinsky is one in every of my favourite composers. He’s a genius. I nonetheless consider that The Ceremony of Spring is among the most essential orchestral items within the twentieth century. There’s a robust pulse and an irregularity in Stravinsky that I actually like; you are all the time feeling that it is altering and providing you with one thing new. Latin American music could be very common, however in the event you analyze my music, rhythmically talking, it’s very irregular.

You alter meters lots.

Sure, and that is one thing that I discovered from Stravinsky. However it’s a must to perceive that we now have the best to soak up these composers. The [perception] is, “Oh, you are a Mexican, so you can not tackle Beethoven.” However Beethoven is common. He’s as essential to me as he’s to the German individuals. I additionally come from this European custom; the Spanish had been right here in Mexico. It is a huge drawback once you speak about borders in music. There are not any borders. Mahler belongs to me. Why not?

And so do György Ligeti and Olivier Messiaen — I hear little essences of these modernist composers in your ballet, and within the violin concerto Altar de Cuerda. You’re agile at mixing avant-garde and European classical traditions with Latin American people kinds. Do you’ve gotten a way of what your personal music appears like?

It’s tough to elucidate in a rational method, nevertheless it comes very pure. I’m absorbing every little thing. It is simply there, it is a part of who I’m, and Debussy is as essential as Perez Prado or mariachi music. If I have to have that type of affect for a particular purpose, I’ll use it. For instance, within the fifth motion of my ballet — the protest part — there’s a samba. Nevertheless it’s not there as a result of I need to sound Latin American through the use of a Brazilian samba. There’s a political purpose to make use of it.

I discover the aspect of rhythm is so robust in your music. In works like Kauyumari, Yanga, Téenek and particularly the trumpet concerto Altar de Bronce, the beats make you need to shake your hips.

I prefer to work with rhythm; it comes naturally. And I like to bop. In all probability, in my previous life, I was a flamenco dancer.

How did a few of these rhythms get to Mexico within the first place?

From Africa. Individuals overlook that within the sixteenth century, there was a really robust African affect in Mexico, and instantly the African slave inhabitants blended with the Indigenous populations and with the Spanish. All these cultures blended collectively was very robust in Mexico — a melting pot. When you go to Vera Cruz, you dance danzón. There are such a lot of issues that stem from Africa.

So you’ve gotten all of those Afro-Cuban and Indigenous Latin American rhythms in your music. How laborious is it to get orchestral musicians, steeped in Brahms and Beethoven, to play these grooves with soul?

If the music is well-written, it’s going to talk. I imply, you do not have to be Russian to play The Ceremony of Spring. You do not have to be Hungarian to play Bartók. I bear in mind listening to Beethoven by [Venezuela’s] Simon Bolivar Symphony, carried out by Dudamel — and wow, what a model of Beethoven. Music is a common language.

With conductor Gustavo Dudamel wanting on, Ortiz takes a bow after a efficiency of her music by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Dustin Downing/Los Angeles Philharmonic

disguise caption

toggle caption

Dustin Downing/Los Angeles Philharmonic

By my rely, since 2020 you’ve gotten had 10 main orchestral premieres — half of them carried out by Gustavo Dudamel — and that is not counting the world premiere of your cello concerto for Alisa Weilerstein, or your non-orchestral premieres. That’s plenty of music. What does that say about your profession?

It is very thrilling. When you had requested me this query 20 years in the past, I’d by no means have imagined that I’d be on this place, particularly right here in Mexico. I don’t understand how I did it, actually. However I can inform you that I labored very, very laborious. It was a novel alternative once I wrote Téenek for Gustavo — that was my first piece for him, and I put all my effort into writing a great piece, as a result of I knew that it was going to be one thing that might both open the door or shut it.

Are you on the peak of your profession proper now?

I do not know, however I am very completely happy proper now, and I’ll inform you why: All composers want good performers to play their music. It’s the solely method we will be taught, by listening to our music. That is why I discuss to Gustavo concerning the want for a pan-Latin American initiative, as a result of consider me, the alternatives listed here are 10 occasions more durable than in different international locations.

Why is that?

As a result of we do not have as many orchestras as you do within the U.S., or as many alternatives. Once I was a scholar, I wrote my first orchestral work beneath the steering of Mario Lavista. And I used to be determined to listen to my piece. There was no orchestra on the college, in order that was not an choice. However you understand what I did? I went to the Mexico Philharmonic Orchestra — knowledgeable orchestra — with my rating in hand and I mentioned, “I need to communicate to the maestro.” They mentioned, “Do you’ve gotten an appointment?” I mentioned, “No. I’ll wait.”

I stayed for 2 hours to talk with Herrera de la Fuente. We met in his workplace and I informed him, “I need to hear my piece. That is all I want. I am a scholar, I need to grow to be a composer, and I need to hear it desperately.” He appeared on the rating and mentioned, “We’ll name you.” Three months later, I acquired a name: “We’re going to play your piece.” That was the one method I might hear my music.

For me, the three items in your latest album with Dudamel main the LA Phil mark a excessive level in your profession. There’s the quick orchestral present piece Kauyumari, the various and deeply thought-about violin concerto Altar de Cuerda, and the expansive, politically charged ballet Revolución Diamantina, which interprets as “Glitter Revolution” in English.

This is the reason I really like the LA Phil and Gustavo, as a result of they requested me what I want to write. [I said,] “I need to write a ballet.” And Gustavo mentioned, “Why don’t you write one thing together with choir, as a result of we need to pair your piece with Beethoven’s Ninth.” I informed them it was going to have a really political theme, that I wanted to precise the femicide state of affairs that’s insufferable right here in Mexico. They usually mentioned, “Sure, do it.”

YouTube

Within the notes for the album, you point out that writing the ballet compelled you to achieve “past the aesthetic languages I do know, by experimenting with new instruments.” Are you able to say extra concerning the methods you needed to be taught in an effort to write this piece?

I used to be exploring issues like whispering and amplified voices, not simply singing — making noises, protesting and shouting slogans. Shouting issues like, “Con ropa o sin ropa, mi cuerpo no se toca” [“With or without clothes, my body is not touched”]. It was completely out of my consolation zone; I by no means wrote music based mostly on a avenue protest.

For instance, the fourth motion — it’s very Stravinskian in some sections, however in others is the depiction of home violence. And I used to be making an attempt to see how I might make the violence stronger and stronger within the music by elevating the extent of sound till you get to “pa, tu, pa, ta,” which represents the combating. I used to be experimenting with the voices in a percussive method — very completely different within the context of orchestral music, and within the context of a ballet.

The themes of gender inequality within the ballet make me consider your orchestral work Clara, impressed by the pianist-composer Clara Schumann, the overshadowed spouse of composer Robert Schumann. You’ve mentioned about this piece: “All through historical past, girls have needed to overcome main obstacles marked by gender variations. There are various of us who’ve rebelled in opposition to these evident types of injustice and struggled to achieve recognition and a spot in society.” That makes me surprise in the event you, your self, have needed to overcome related obstacles as a lady composer?

Sure, generally. I bear in mind I used to be very younger, presenting a clarinet piece to a composition trainer, and the man noticed the rating and he mentioned, “Take into consideration Clara Schumann and Robert Schumann. Robert is healthier. Take into consideration Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn. Felix is a lot better. Take into consideration Alma Mahler and Gustav Mahler. Gustav is healthier. Do not you assume girls compose like they’re cooking a recipe?” When he mentioned that, I took my rating and I left the room and by no means got here again.

Virtually each girl composer I’ve talked to has a narrative. Kaija Saariaho informed me about professors who did not need to train her as a result of she was fairly and would get married and have youngsters. Meredith Monk recalled males who made her really feel like there was one thing improper along with her as a result of she had a imaginative and prescient of what she wished to do. However each of them additionally mentioned there was no method anybody might cease them.

That is appropriate. I imply, I used to be very indignant, however he did not cease me from writing music. I all the time face the issue of being a lady composer, but additionally a Latin American composer. I bear in mind once I was in Darmstadt, Germany [a hotbed of experimental music], one performer got here to me and mentioned, condescendingly, “Oh, you are from Mexico — so that you’re the type of Mexican composer who works with melody and rhythm and concord.” And I mentioned, “Sure. Is there an issue with that?” I like music. And music is about melody, rhythm, concord, chords — not solely about texture and noise.

You need to really feel a sure sense of delight, and accountability, now that you are taking on the place of Composer’s Chair at Carnegie Corridor this season. What sort of freedom does this residency supply?

Numerous freedom. I proposed a sequence of concert events they usually allowed me to collaborate with completely different ensembles, just like the Ensemble Join — that live performance will characteristic Latin American music. If I can assist promote these unimaginable composers, I’ll do this. We’re additionally doing an interdisciplinary mission referred to as Can We Know the Sound of Forgiveness, a collaboration with visible artist James Drake; the author Benjamin Alires Sáenz from El Paso, Texas; Alejandro Escuer, the Mexican flutist; and The Crossing choir. I used to be capable of suggest that mission, which was properly acquired by the establishment.

What sort of recommendation are you giving your college students on the Nationwide Autonomous College in Mexico Metropolis who need to have a profession as a composer?

I all the time inform them they should work very laborious and have plenty of self-discipline. Expertise is essential, after all, nevertheless it’s not solely about expertise. It’s a must to put all your soul into your work. Each single piece must be a winner, irrespective of if it is for solo clarinet or for orchestra. One other essential factor is, they should stay their lives very intensely, as a result of that is the gasoline in your creativity, for all times itself.

I’ve to inform you, I really feel I made the best choice to remain on this nation. Once I completed my PhD in London, I used to be considering possibly I ought to keep there due to the alternatives. I used to be additionally provided to show at Indiana College and different locations within the U.S. [But] I all the time thought that it was essential for me to be right here in Mexico. As a result of the Autonomous College is a free college — it’s robust to get in, however when you’re in, you don’t pay a single peso — so individuals come from many various financial ranges. For me, it is essential, as a result of I really feel that I am making a contribution to my nation and to my very own individuals. I really feel like I am placing a seed in every of them.

What sort of recommendation are you giving to your self nowadays, given how busy you’re writing music and navigating your rising status?

Typically I believe: “Why did not this occur years in the past? It is occurring once I’m turning 60?” So I’ve to be very clever with my time. I’ve to deal with myself. I train — I am sporting pants proper now as a result of I got here from the fitness center. I’ve to stay my life as properly, each second. I’ve to benefit from the easy issues. If I am seeing a good friend, I’ve to get pleasure from that second. If I am studying a guide, I’ve to get pleasure from that.

Additionally, be delicate about what’s occurring. Maybe 10 years in the past, I’d have been extra cautious concerning the issues I speak about, however not now. I am ready that if I want to speak about feminism, I’ll do it. If I want to speak about local weather change, I’ll do it, as a result of that issues to me. It is all part of our life.